A revenue source that is repetitively brought forward in the Vermont legislature is the so-called “cloud tax.” This tax is traditionally thought of by many as a tax on the tech sector, however, the growing use of online-based services means every Vermonter and Vermont business owner has reason to be concerned. We break down some of the frequently asked questions around this continually proposed tax below. If you’re concerned, please reach out to our team at [email protected].

What is the “cloud” that they want to tax?

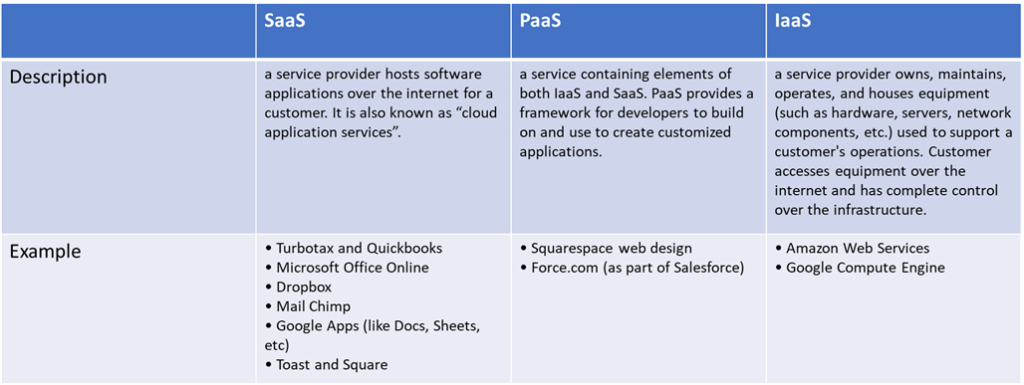

Cloud-based services are broken down into three categories; software as a service (SaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). When all three categories are combined, this is about 99.99% of activity on the internet. In the past, legislative interest has been solely on SaaS, however, in a more recent proposal, it went beyond this to all three categories.

Isn’t some software already taxed?

Yes, if the software is downloaded onto a device, that is considered “tangible personal property,” the same as if you went out and bought it on a CD format from a local retailer.

So the legislature would create a new tax?

A cloud tax would not be a new tax explicitly created for internet services; rather, it adds internet services to the list of transactions covered by Vermont’s existing sales and use tax. This means that Vermonters would be liable for a 6% tax on their internet-based services and, in areas with a local option tax, an additional 1% tax.

How much will this cost the Vermont economy?

This could pull upwards of $20 million dollars from the Vermont economy, according to the most recent JFO modeling. However, we believe this modeling does not fully capture how online-based our economy is, especially post-pandemic. In talking to members, we’ve heard that even our smallest members are paying at least $20,000 a year for internet-based services to compete in this modern economy. By JFO’s own presentation to the legislature, 83% of all company workload will be stored on the cloud, and 67% of all enterprise software is estimated to be cloud-based.

Wait, Vermont doesn’t tax services, (with a few exceptions) why is this different?

That’s a great question because this shouldn’t be any different. Vermont does not tax services, and this would be a massive service sector to start taxing.

So, might this violate federal interstate commerce laws?

Because this is a one-off attempt at finding more revenue and not part of a larger push to tax services, the state risks violating the Internet Tax Freedom Act (ITFA) by trying to discriminate against internet-based commerce for tax not levied on comparable in-person-based commerce. This legislation could also violate the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution by treating services from outside the state differently than those rendered inside the state.

Well, other states have cloud taxes…

Sure, however, rather than looking at whether other states have such a tax as an indicator of if we should tax internet-based services, we should look at our tax mix and compare it to theirs. Many states that have a cloud tax already have taxes on services, while Vermont does not tax services. Proponents will often cite Washington as an example of a state that has this tax while not acknowledging that Washington does not have an income tax.

In what situation would LCC allow a cloud tax?

LCC’s opposition to the cloud tax is not dogmatic, and there could be instances in which a cloud tax could be reasonable. For instance, other states have moved to tax cloud-based services as a larger part of tax structure reform. Vermont discussions around cloud taxation have generally not been as a result of larger-scale tax reform, though some proponents have claimed this is part of broadening the tax base to create more stability. A one-off creation of a new tax on services should not be mistaken for any type of tax structure reform.